Understanding HTTP

HTTP Intro

HTTP Protocol

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the foundation of data communication on the web. It's stateless, meaning it doesn't remember past interactions, and each request is independent.

Statelessness

Each HTTP request carries all necessary information (like headers, URLs, and methods), and after the server responds, it forgets about the request. This simplifies server architecture, making it easier to scale because there’s no need to store session information. However, developers often implement state management techniques (like cookies, sessions, or tokens) to maintain continuity, such as for user logins or shopping carts.

Client-Server Model

HTTP operates on a client-server model. The client (typically a web browser or application) sends a request to the server, which processes the request and sends back an appropriate response (like a webpage, data, or an error message). HTTP communication is always initiated by the client.

HTTPS

HTTPS is a secure version of HTTP, with added security features like encryption and security certificates (such as TLS), but the core principles remain the same.

Transmission Protocol

HTTP uses the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) for communication. TCP ensures reliability and doesn't allow messages to be lost in transmission, which is why it's preferred over UDP for HTTP traffic.

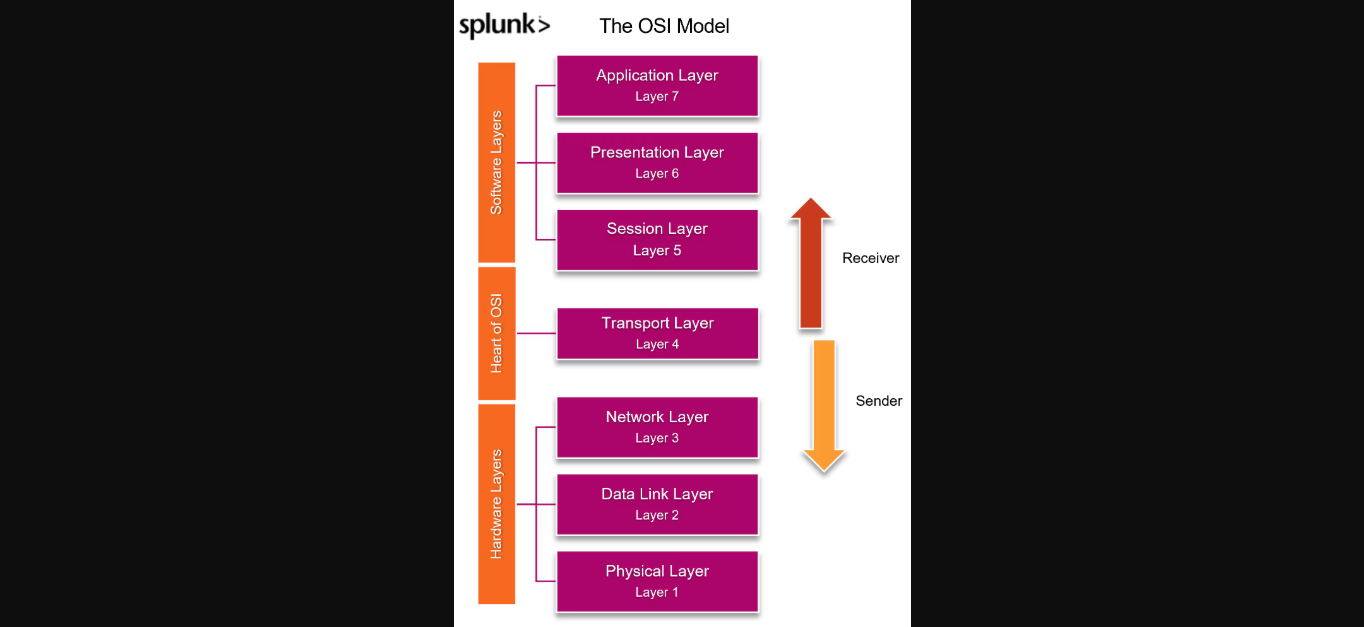

OSI Model

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model is referenced in discussions about sending and receiving data over a network. HTTP operates at the application layer (Layer 7) in the OSI model, while TCP works at a lower layer (Layer 4).

TCP Handshake

HTTP relies on TCP, which uses a three-way handshake to establish a connection. This is a network-level concept, and understanding it can be useful but is often outside the scope of web development discussions.

Evolution of HTTP

The HTTP protocol has evolved over the years to improve performance and efficiency. Here's a summary of its key changes:

HTTP 1.0

- Connection Handling: In HTTP 1.0, each request opened a new connection.

- Drawbacks: This approach led to inefficiencies as a new connection had to be established and closed for every request and response, which slowed down performance.

HTTP 1.1

- Persistent Connections: Introduced persistent connections, allowing multiple requests and responses over the same TCP connection. This significantly improved performance.

- Additional Features:

- Chunk Transfer Encoding: Improved data transfer efficiency.

- Better Caching Mechanisms: Optimized how resources are cached, reducing the need for repeated requests.

HTTP 2.0

- Multiplexing: Allowed multiple requests or responses over a single connection.

- Binary Framing: Replaced text-based framing with binary, improving efficiency.

- Header Compression: Utilized HPACK to compress headers and reduce overhead.

- Server Push: Allowed servers to send resources to clients before the client explicitly requested them.

HTTP 3.0

- Built on QUIC: HTTP 3.0 is built on the QUIC protocol, which operates over UDP rather than TCP.

- Improvements:

- Faster Connection Establishment: QUIC reduces latency by establishing connections more quickly.

- Better Packet Loss Handling: Improved resilience to packet loss.

- Continued Multiplexing: Maintains multiplexing without the head-of-line blocking issue present in HTTP 2.0.

HTTP Messages

HTTP messages can be of two types: Request Messages and Response Messages. Here's a breakdown of each.

Request Messages

A request message is sent by the client to the server. It typically contains the following components:

- Request Method: The action the client wants to perform (e.g., GET, POST, PUT).

- Resource URL: The specific resource the client is requesting from the server.

- HTTP Version: Specifies the version of HTTP being used (e.g., HTTP/1.1).

- Host: The domain of the server the client is communicating with (e.g.,

example.com). - Headers: Key-value pairs containing additional information like content type, authorization, etc.

- Request Body: Data that the client wants to send to the server (optional).

Here's an example of what a request message might look like:

GET /path/to/resource HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Content-Type: application/json

Authorization: Bearer <token>

{ "key": "value" }- Request Method:

GET - Resource URL:

/path/to/resource - HTTP Version:

HTTP/1.1 - Host:

example.com - Headers:

Content-Type,Authorization, etc. - Request Body:

{ "key": "value" }(if applicable)

Response Messages

A response message is received by the client from the server. It typically contains the following components:

- HTTP Version: The version of HTTP used for the response (e.g., HTTP/1.1).

- Status Code: A numeric code indicating the result of the request (e.g., 200 for success).

- Response Headers: Key-value pairs containing metadata about the response.

- Response Body: The data sent back from the server (e.g., HTML content, JSON data).

Here's an example of what a response message might look like:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 123

{ "status": "success", "data": { "key": "value" } }- HTTP Version:

HTTP/1.1 - Status Code:

200 OK - Response Headers:

Content-Type,Content-Length, etc. - Response Body:

{ "status": "success", "data": { "key": "value" } }

HTTP Headers

Headers are a critical part of both request and response messages. They provide metadata and additional context about the request or response. We'll cover headers in more detail later in this series.

Summary

- Request Message: Sent by the client to request a resource, including method, URL, version, headers, and optional body.

- Response Message: Sent by the server in reply to a client request, including version, status code, headers, and body.

Why Do We Need HTTP Headers?

HTTP headers are a crucial part of both request and response messages. They provide key-value pairs of metadata about the request or response. Here are some important points regarding HTTP headers:

What are HTTP Headers?

- HTTP headers are key-value pairs of parameters that are sent in the request or received in the response.

- They are not part of the body or the URL but act as metadata about the request or response.

Why Do We Need HTTP Headers?

We could technically send all the values inside the URL or request body, but HTTP headers provide a separate section for metadata. This separation offers several benefits:

Separation of Data and Metadata: Just like a postal service uses an address on the outside of a package to guide its journey, HTTP headers carry metadata about the request or response. This makes it easier to handle, without having to open the data (body) every time.

Efficiency: Including metadata (such as the recipient's address or a tracking number) on the outside of a package avoids the need to open and check the package multiple times. Similarly, HTTP headers allow quick access to critical information without the need to process the request body each time.

Flexibility: HTTP headers enable different aspects of the request or response to be processed separately, improving flexibility and efficiency in managing requests.

Types of HTTP headers

The client to the server to provide some kind of information about the request itself. It could be user-agent, which identifies what kind of client is that. It could be a browser, a Postman, a server, or a mobile app.

- Authorization: Sends different credentials like bar token to the server to identify the user.

- Accept headers: Provides information like what kind of content we are expecting, whether it is JSON, text, or an HTML file.

Request headers help the server understand the client's environment, preferences, and capabilities.

General headers

Used in both request and responses, containing metadata about the message itself.

- For example: Date of the message, caching mechanisms like no cache or max age, and connection information like whether to keep the connection alive or to close it.

Representation headers

Primarily deal with the representation of the resource being transmitted (whether request body or response message).

- Content-Type: Describes the media type of the request or response.

- Content-Length: Describes the size of the resource in bytes.

- Content-Encoding: Specifies any encoding like Gzip or Deflate.

- Etag: A unique identifier, mostly used for caching.

Security headers

Used to enhance the security of the request and response by controlling behaviors like content loading, cookies, and encryption.

- HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security): Ensures that the client only communicates with the server over HTTPS, preventing protocol downgrade attacks.

- Content Security Policy (CSP): Restricts sources from which content like JavaScript, CSS, and images can be loaded, preventing cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks.

- X-Frame-Options: Prevents the webpage from being embedded in an iframe, mitigating clickjacking attacks.

- X-Content-Type-Options: Ensures that the browser does not try to guess the MIME type of the content, preventing MIME-type sniffing attacks.

- Cookie with HTTPOnly or Secure Flags: Secures cookies by making them inaccessible with JavaScript and ensuring they are sent over HTTPS.

Extensibility

HTTP is highly extensible because headers can be easily added or customized without altering the underlying protocol.

- For example, custom headers like

X-Custom-Headercan be created for specific application use cases.

Remote Control

HTTP headers act like a remote control on the server-side. They allow the client to send instructions or preferences to the server, influencing how the server responds or processes requests.

- Content-Type Negotiation: Clients can request specific formats using the Accept header, and the server can respond with the appropriate format.

- Caching and Expiration Control: The server can use headers like Cache-Control or Expires to control how long a resource should be cached by the client.

- Authentication: The client can authenticate itself to the server through the Authorization header, influencing Access Control decisions.

HTTP Methods

HTTP methods define the intent of an interaction between a client (like a browser or API consumer) and a server. Each method represents a specific action and provides clear semantic meaning. Below are the common HTTP methods:

1. GET

- Intent: Fetch data from the server.

- Side Effects: Does not modify any data on the server.

- Typical Use Case: Requesting a webpage or retrieving some data.

2. POST

- Intent: Create data on the server.

- Side Effects: It typically involves modifying data on the server.

- Body: Contains data to be sent to the server (e.g., user input or form submissions).

- Typical Use Case: Submitting a form or creating a new resource.

3. PATCH

- Intent: Update data partially on the server.

- Side Effects: Modifies some part of the resource on the server.

- Body: Contains the data to update specific fields.

- Typical Use Case: Updating a user's profile (e.g., changing a user's name).

4. PUT

- Intent: Completely replace data on the server.

- Side Effects: The request body completely replaces the existing resource.

- Body: Contains the full data to replace the previous instance.

- Typical Use Case: Replacing an entire user profile or resource.

Note: Though PUT is often used when PATCH should be used, the thumb rule is to use PATCH unless there's a specific reason to replace the entire resource with PUT.

5. DELETE

- Intent: Remove a resource from the server.

- Side Effects: Deletes the specified resource.

- Typical Use Case: Deleting a user or any other resource from the server.

Idempotent vs Non-Idempotent HTTP Methods

In the context of HTTP methods, the concept of idempotent and non-idempotent refers to whether repeated requests with the same parameters yield the same result.

1. Idempotent Methods

An idempotent HTTP method can be called multiple times, and we can expect the same result every time. The key idea is that the outcome will not change, even if the request is repeated. Common idempotent methods include:

GET:

- Intent: Fetch data from the server.

- Explanation: No matter how many times you send the same GET request, the result (data) should be the same. It does not modify any data on the server.

PUT:

- Intent: Completely replace data on the server.

- Explanation: Replacing a resource with the same data multiple times will always result in the same outcome. The resource will be replaced with the same data, so the outcome is identical each time.

DELETE:

- Intent: Remove a resource from the server.

- Explanation: A resource can only be deleted once. After that, attempting to delete it again will always result in the same outcome—nothing to delete.

2. Non-Idempotent Methods

A non-idempotent HTTP method produces different results if the same request is repeated. This means that performing the request multiple times can result in different outcomes. Common non-idempotent methods include:

- POST:

- Intent: Create data on the server.

- Explanation: If you send the same POST request multiple times, it will result in different outcomes. For example, creating a new note. The first request creates a note, and subsequent requests will create additional notes, producing different results.

OPTIONS Method and CORS Workflow

Introduction

The OPTIONS method plays a crucial role in the Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) workflow, which is a security mechanism that governs how browsers handle requests for resources across different origins. CORS is part of the same-origin policy enforced by browsers, which restricts a web page from making requests to a domain other than the one that served the web page.

OPTIONS Method

The OPTIONS method is primarily used to fetch the capabilities of a server for a cross-origin request. You might not use the OPTIONS method directly as a developer, but you will encounter it occasionally in your browser’s network tab as part of pre-flight requests.

Pre-flight Requests

A pre-flight request is an HTTP request made before the actual request in order to determine the allowed methods, headers, and other capabilities supported by the server. This helps ensure that the actual request can be safely made without violating CORS restrictions.

Same-Origin Policy and CORS

- Same-Origin Policy: By default, browsers follow the same-origin policy, which restricts web pages from making requests to a domain different from the one serving the web page.

- CORS: CORS allows servers to specify who can access their resources and how. It enables cross-origin requests when the browser checks whether the server includes the correct headers in its response.

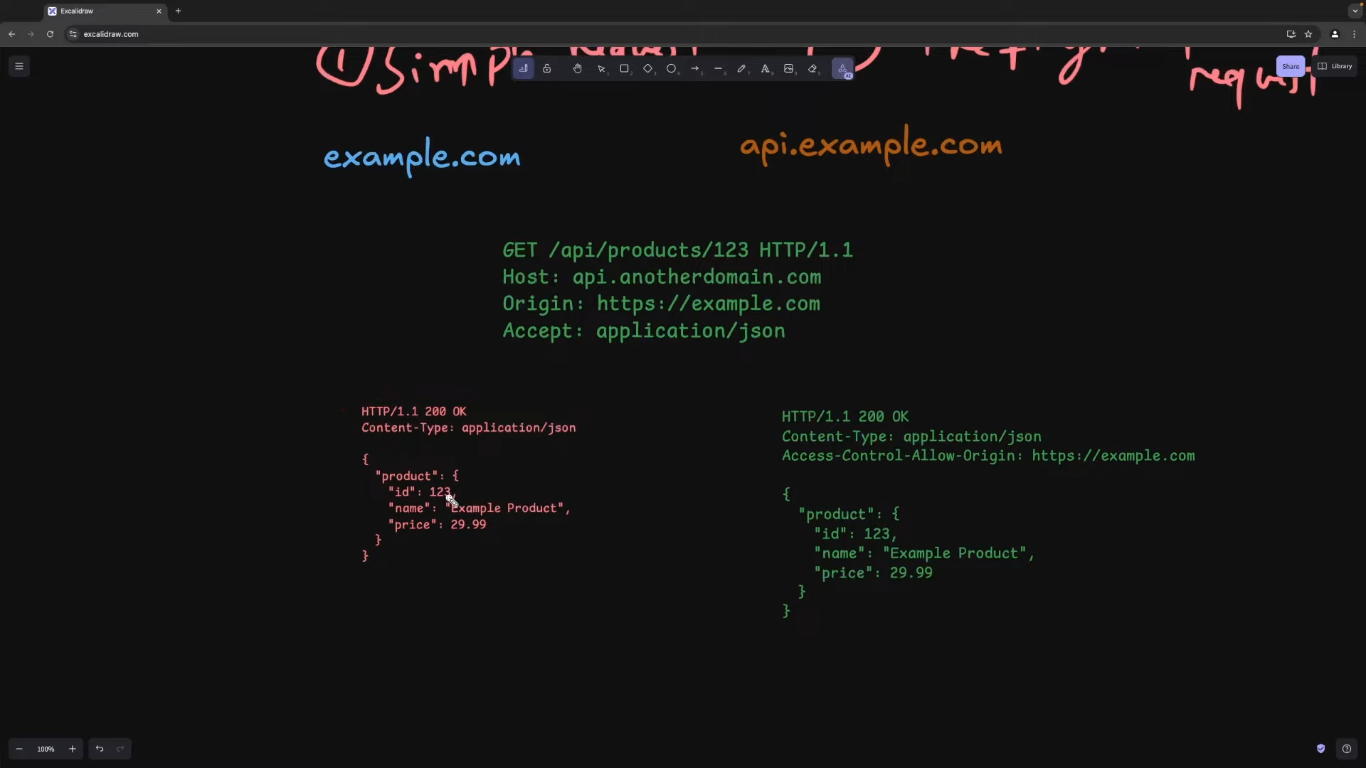

Simple Request Flow

- Client Request: The frontend, at

example.com, makes aGETrequest to a server atapi.example.com. - Server Response: The server checks for the origin of the request and includes the

Access-Control-Allow-Originheader in its response if the origin is allowed. - CORS Headers: The browser checks the response for the appropriate CORS headers (

Access-Control-Allow-Origin). If present, the request is passed through; otherwise, it is blocked.

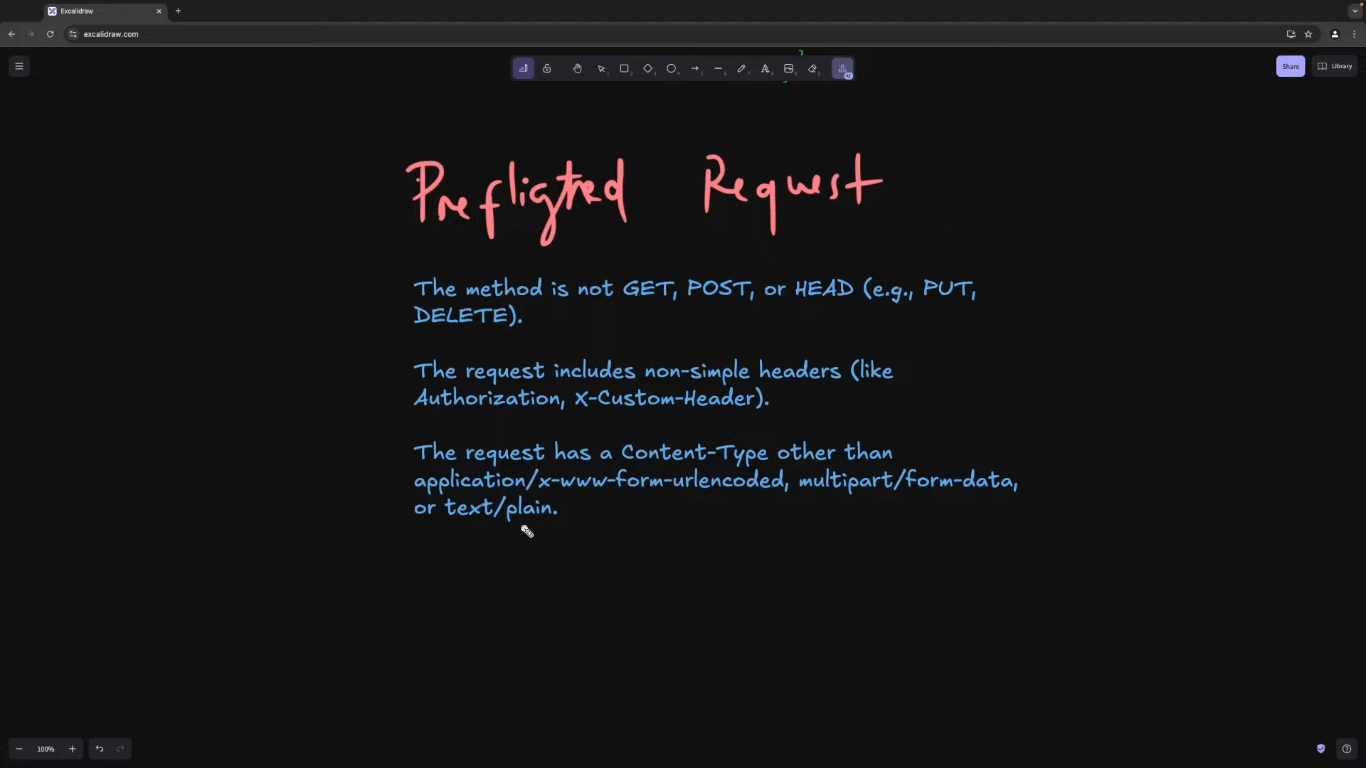

Pre-flight Request Flow

A request qualifies as a pre-flight request if it meets the following conditions:

A request qualifies as a pre-flight request if it meets the following conditions:

- Cross-origin Request: The request is made from a different origin (e.g.,

example.comtoapi.example.com). - Method: The request uses methods other than

GET,POST, orHEAD(e.g.,PUT,DELETE). - Custom Headers: The request includes non-simple headers (e.g.,

Authorizationheader). - Content-Type: The request uses a content type other than

application/x-www-form-urlencoded,multipart/form-data, ortext/plain.

Example of a Pre-flight Request

The pre-flight request is made with the OPTIONS method and looks like this:

OPTIONS /resource HTTP/1.1

Host: api.example.com

Origin: http://example.com

Access-Control-Request-Method: PUT

Access-Control-Request-Headers: AuthorizationThis request inquires whether the server supports a PUT request and whether it accepts the Authorization header.

Example of a Pre-flight Response

If the server supports the cross-origin request, it responds with the following headers:

HTTP/1.1 204 No Content

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: http://example.com

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: PUT, DELETE

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Authorization

Access-Control-Max-Age: 86400- Access-Control-Allow-Origin: Specifies the allowed origin.

- Access-Control-Allow-Methods: Specifies the allowed HTTP methods.

- Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Specifies the allowed headers.

- Access-Control-Max-Age: Indicates how long the results of the pre-flight request can be cached (e.g., for 24 hours).

HTTP Response Codes

HTTP response codes exist to communicate the result of a request in a standardized way. They help clients determine whether a request was successful, resulted in an error, or requires further action, without having to examine the body of the response.

Why are Response Codes Needed?

- Quick Status: Response codes allow clients to determine the success or failure of a request without needing to interpret the entire response.

- Error Handling: Specific codes help clients handle errors, e.g., logging users out on a 401 Unauthorized error or prompting for corrections on a 400 Bad Request error.

- Standardization: Response codes are standardized across all web services, ensuring consistency regardless of the platform or language used.

Categorizing Response Codes

Response codes are three-digit numbers categorized by their first digit:

- 1xx (Informational): Request received, continuing process.

- 2xx (Success): Request successfully received, understood, and accepted.

- 3xx (Redirection): Further action needed to fulfill the request.

- 4xx (Client Error): The client seems to have made an error.

- 5xx (Server Error): The server failed to fulfill a valid request.

1xx - Informational Responses

These codes indicate that the server has received the request and the client can proceed. Commonly used during large uploads or protocol switching.

- 100: Continue – The server has received the headers, and the client can proceed with the request body.

- 101: Switching Protocols – The server is switching protocols as requested by the client.

2xx - Success Responses

These codes indicate that the request was successful.

- 200: OK – The request was successful, and the server is returning the requested resource or performing the action.

- 201: Created – The request has been fulfilled, and a new resource has been created.

- 204: No Content – The request was successful, but there is no content to return (e.g., for DELETE requests).

3xx - Redirection Responses

These codes indicate that further action is needed to complete the request.

- 301: Moved Permanently – The requested resource has been permanently moved to a new URL.

- 302: Found – The requested resource is temporarily located at a different URL.

- 304: Not Modified – The resource has not been modified since the last request, allowing the client to use the cached version.

4xx - Client Error Responses

These codes indicate an issue with the client’s request.

- 400: Bad Request – The server could not understand the request due to invalid syntax.

- 401: Unauthorized – Authentication is required, and the client did not provide valid credentials.

- 403: Forbidden – The server understood the request but refuses to authorize it.

- 404: Not Found – The requested resource could not be found on the server.

- 405: Method Not Allowed – The HTTP method used is not allowed for the requested resource.

- 409: Conflict – There is a conflict with the current state of the resource (e.g., duplicate data).

- 429: Too Many Requests – The client has sent too many requests in a given amount of time.

5xx - Server Error Responses

These codes indicate an issue with the server processing the request.

- 500: Internal Server Error – The server encountered an unexpected condition preventing it from fulfilling the request.

- 501: Not Implemented – The server does not support the functionality required to fulfill the request.

- 502: Bad Gateway – The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, received an invalid response from the upstream server.

- 503: Service Unavailable – The server is temporarily unable to handle the request, usually due to high traffic or maintenance.

- 504: Gateway Timeout – The server, while acting as a gateway or proxy, did not receive a timely response from the upstream server.

HTTP Caching

HTTP caching is a technique used to store copies of responses in order to reduce the need for repeated requests to the server. This helps improve load times, reduce bandwidth usage, and lessen the server load, as the client can reuse cached data when it hasn't changed.

How HTTP Caching Works

Initial Request:

When the client first makes a request for a resource, the server responds with the data and includes caching-related headers in the response:Cache-Control: Specifies how long the resource should be cached (e.g., for 10 seconds).ETag: A hash of the resource, allowing the server and client to check if the resource has changed.Last-Modified: The last modification time of the resource, which the client can use to determine if the resource is up-to-date.

Subsequent Requests:

For future requests, the client can check if it has a cached version of the resource by sending headers such as:If-None-Match: The client sends theETagvalue of its cached resource. If it matches the server’s currentETag, the server knows the resource hasn't changed.If-Modified-Since: The client sends the last modification date of its cached resource. If the resource hasn't been modified since that date, the server will return a304 (Not Modified)response, indicating the client can use its cached version.

Server Response:

- If the resource hasn't changed, the server responds with a

304status, telling the client to use the cached version. - If the resource has changed (e.g., after an update), the server responds with a

200status and the new resource along with a newETagandLast-Modifiedheader.

- If the resource hasn't changed, the server responds with a

Updating Cache:

After an update to the resource, the server sends a newETagvalue and aLast-Modifiedtime, and the client uses the new data in subsequent requests.

Challenges in Production

In production, handling these headers manually can get complicated. Incorrect handling (e.g., failing to update the ETag) can lead to clients using outdated resources. Modern solutions like React Query simplify client-side caching, providing more control over caching, such as setting intervals for data refetching and cache expiration. However, HTTP caching remains a good solution for simpler use cases.

HTTP Content Negotiation

Content negotiation is a mechanism in HTTP where the client and server agree on the best format for exchanging data. The client can specify its preferred data format (e.g., JSON, XML, HTML) and the server will respond with a compatible format or a fallback format if the preferred one isn't available.

Types of Content Negotiation

Media Type Negotiation

The client specifies the desired data format using theAcceptheader. For example:Accept: application/json(JSON format)Accept: application/xml(XML format)

Language Negotiation

The client can request content in a specific language using theAccept-Languageheader. For example:Accept-Language: en(English)Accept-Language: es(Spanish)

Encoding Negotiation

The client can specify which encoding it supports using theAccept-Encodingheader. For example:Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate(for compression formats)

This is particularly useful for HTTP compression, where the server can compress the response before sending it to the client.

Demo of Content Negotiation

Default Request:

The client sends:Accept-Language: en(English)Accept: application/json(JSON format)Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate(compression formats)

The server responds with content in English, formatted as JSON, and optionally compressed.

Language Change:

If the client changes theAccept-Languageheader to Spanish (Accept-Language: es), the server responds with the content in Spanish.Format Change:

The client can change theAcceptheader toapplication/xmlto request the response in XML format instead of JSON. If the client also requests Spanish (Accept-Language: es), the server responds with content in Spanish and XML format.

Benefits of Content Negotiation

Content negotiation allows:

- Clients to specify their preferences for the data format, language, and encoding.

- Servers to respond with the most suitable content based on the client's preferences.

- Simplified client-server interactions by enabling flexible data exchange.

HTTP Compression

HTTP compression is a technique used to reduce the size of the data being transferred between the server and the client. It helps minimize bandwidth usage and improves loading times, especially for large files.

Why Do We Need Compression?

Compression is important because large files can consume a lot of bandwidth, making data transfer slower and less efficient. By compressing responses, the server reduces the amount of data to be transferred, improving speed and reducing costs.

How HTTP Compression Works

Request:

The client indicates support for compression by including theAccept-Encodingheader in the request. For example:Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Response:

The server checks theAccept-Encodingheader to determine the formats supported by the client. If the client supportsgzip, the server can respond with a compressed version of the file.Compression Example:

When the server responds with a large file (e.g., 11,000 entries), it is typically compressed to reduce the size. For instance:- Without compression: The file size could be 26 MB.

- With compression (gzip): The file size could be reduced to 3.8 MB.

Decompression:

The client (usually a web browser) can then decompress the file on its side and use it as usual, getting the same response but with a reduced data size.

Benefits of HTTP Compression

- Reduced File Size: Compressing large files can significantly reduce the amount of data transferred over the network.

- Improved Speed: Smaller file sizes result in faster downloads, improving user experience.

- Reduced Bandwidth Usage: Compression saves bandwidth and reduces costs for both the client and the server.

Persistent Connections and Keep-Alive

Persistent connections are a crucial feature in HTTP that help reduce the inefficiency of repeatedly establishing and closing TCP connections for each request-response cycle. They were introduced in HTTP 1.1 to improve the performance of web communications.

Why Persistent Connections?

- Before HTTP 1.1: In HTTP 1.0, each request-response cycle required a new TCP connection to be established. This was resource-intensive and slow.

- With HTTP 1.1: A single TCP connection can be reused for multiple requests and responses, reducing overhead.

Keep-Alive Header

- The

Keep-Aliveheader is used to enable persistent connections. It allows the client and server to reuse the same connection for multiple requests and responses until one side decides to close it. - In HTTP 1.1, persistent connections are the default. You don’t need to do anything explicitly unless you want to specify certain conditions.

Key Points to Remember

Persistent Connections by Default in HTTP 1.1:

- Connections remain open for further requests unless explicitly closed.

- Multiple HTTP requests and responses can be sent over a single connection, reducing latency and resource usage.

Keep-Alive Header:

- While persistent connections are default in HTTP 1.1, the

Keep-Aliveheader can be used to explicitly request that the connection remain open. - The header can also include options, such as:

- How long the connection should stay open (timeout).

- The maximum number of requests that can be sent before the connection is closed.

- While persistent connections are default in HTTP 1.1, the

Closing Connections:

- If a connection is set to close, the connection will be closed after the response is sent.

- This behavior is default in HTTP 1.0 but can still be explicitly enforced in HTTP 1.1.

Multipart Data and Chunked Transfer

Handling large requests (like files) and responses (such as videos, images, or audio) is crucial for efficient web communication. HTTP provides mechanisms like multipart requests and chunked transfer encoding to deal with large data transfers.

1. Multipart Requests (Uploading Large Files)

Multipart requests are used for sending large files from the client to the server. Unlike regular JSON requests, where the data is sent as a single block, multipart requests break the data into parts.

Key Features:

- Binary Data Transfer: The data of the file (binary data) is transferred in separate parts.

- Content-Type: The

Content-Typeheader is set tomultipart/form-data, which indicates that the body contains multiple parts. - Boundary: A boundary is defined to separate different parts in the request body. The boundary is specified using the

boundaryparameter in theContent-Typeheader.

Example:

When uploading a file, the request will have:

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----boundaryValue- The body will contain parts separated by the boundary (e.g.,

----boundaryValue).

This allows the server to reconstruct the file from the individual parts.

2. Chunked Transfer (Receiving Large Responses)

When a server needs to send large responses (such as a large text file), chunked transfer encoding is used to send the data in smaller, manageable chunks.

Key Features:

- Text Event Stream: The response is streamed as

text/event-stream, indicating that the data will be sent in a series of events. - Connection Keep-Alive: The

Connection: keep-aliveheader ensures the connection remains open until the entire response is sent. - Chunked Data: The server sends the response in chunks, and the client appends each chunk to reconstruct the full content.

Example:

- The client sends a normal GET request to the server.

- The server responds with

Content-Type: text/event-streamand keeps the connection open. - The data is sent in chunks, and the client receives and appends these chunks to form the complete response.

This allows for efficient transfer of large files without overwhelming the client or server.

SSL, TLS, and HTTPS

These terms are important for securing communication between a client (like a web browser) and a server. Here's what they mean:

1. SSL (Secure Sockets Layer)

- SSL was the original protocol used to secure communication between clients and servers.

- It encrypts data to protect sensitive information, such as passwords and credit card numbers, from being intercepted by attackers.

- SSL is outdated today due to security vulnerabilities and has been replaced by a more secure protocol, TLS.

2. TLS (Transport Layer Security)

- TLS is the modern, more secure version of SSL.

- It encrypts data in transit, ensuring that communication between the client and server is protected from interception and tampering.

- TLS uses certificates to authenticate the server and establish an encrypted connection, protecting against eavesdropping and data breaches.

- TLS is continuously updated with newer versions for better security. The current recommended version is TLS 1.2 or TLS 1.3.

3. HTTPS (HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure)

- HTTPS is simply HTTP with TLS encryption.

- When you visit a website using HTTPS, the communication between your browser and the server is encrypted using TLS, which prevents attackers from intercepting sensitive information like login credentials.

- HTTPS ensures the security of data during transmission, especially for websites handling private data (such as banking or shopping websites).